introduction

Recent excavations in the Great Temple of Berenike, the first substantial ones since the 19th century, began in early 2011 with several test trenches. These test trenches produced prove for the existence of still undisturbed archaeological layers, notwithstanding excavations conducted here during the 19th century. The Berenike Temple Project aims at a thorough investigation of the temple complex to document its architecture and history, its links with the town and inhabitants and the influence the international character of the town had on its functioning.

Early research in the temple

When Giovanni Batista Belzoni (re)discovered Berenike on 8 October 1818, he found in the centre of the town “…a small temple, nearly covered by the sand…The temple is built of a kind of soft, calcareous, and sandy stone, but decayed much by the air of the sea “. Belzoni estimated the temple to be over 25 meters long. Although his description of the temple plan is somewhat confusing, the sketch he produced gives a fairly accurate view of its general layout. Although he did not see the front wall of the building, he suspected the building to have a large front hall.

In spite of the absence of any digging equipment, which the expedition remarkably failed to bring, Belzoni ordered excavation of a part of the temple, the most visible remnants of a structure on the site. To make matters worse, the absence of potable water in the vicinity forced the expedition to leave the next day. As a result, in the middle of the night and with only the light of the full moon, an Egyptian boy named Mussa started excavating a temple room with a big shell. In the meantime, Belzoni continued to survey the area immediately south of Berenike. Upon his return to Berenike at 10 in the morning, Belzoni found that Mussa had dug a hole, 1.20 m deep, close to a corner of a temple room where he exposed a relief on the wall and unearthed a stela fragment. Upon his return in 1820, the fragment of the red stone stela was the only object from the temple he brought with him to England.

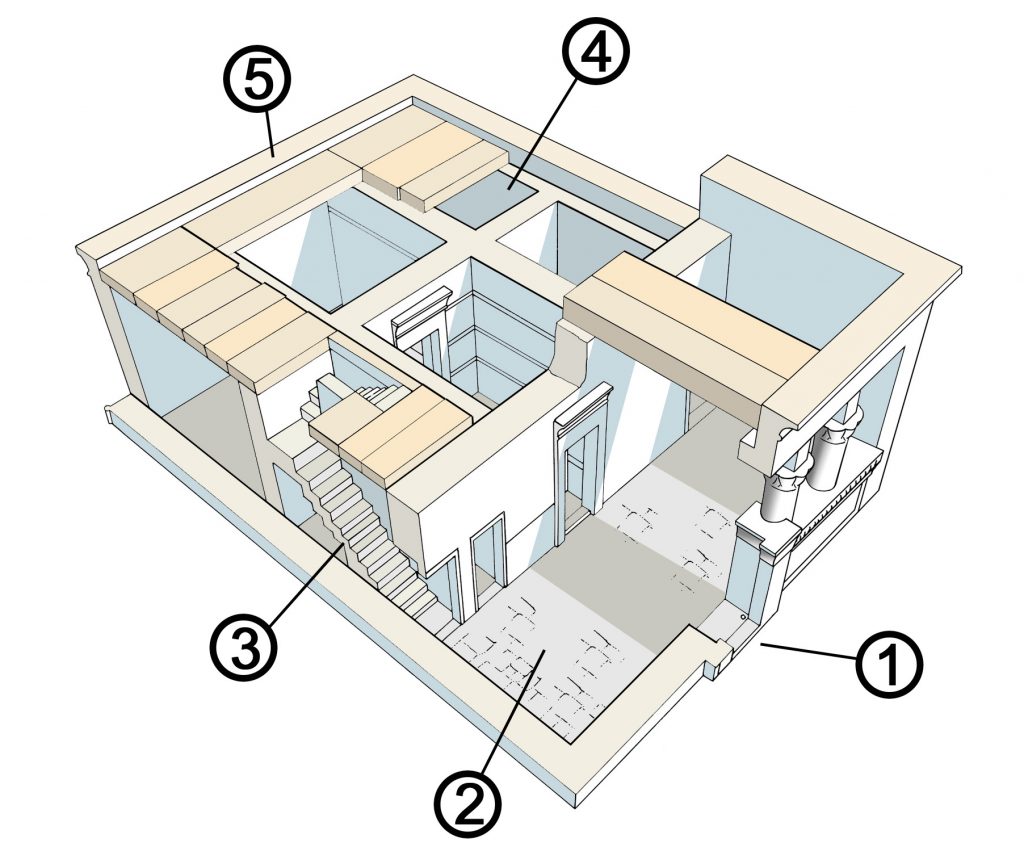

Eight years later, John Gardner Wilkinson visited the site and made the first detailed plan of the town. His notes contain drawings of inscriptions with cartouches, which he thought to be of the emperors Tiberius and Marcus Aurelius . In his Topography of Thebes he described his finds in the temple: “In excavating these chambers (for I did not attempt the portico), I found a Greek dedication to Serapis, the head of a Roman emperor, either Trajan or Adrian, a small fountain, and some rude figures, probably ex votos.”

In 1836 James Wellsted visited Berenike and excavated a small part of the temple. The plan he made is evidence that in this period less than half of the building was visible at the surface. Although he had limited time, Wellsted managed to excavate a large part of room 2, which appeared to have been previously partially excavated, probably by Wilkinson. He found two fragments of a stela with a Greek inscription, containing a dedicatory text of a Ptolemaic king. To access the room Wellsted dislodged several massive roofing stones. On several ceiling blocks in room 2 the hieroglyphic inscriptions were, according to Wellsted, “in a beautiful state of preservation”.

As part of the plan to modernize the Egyptian army, in 1870 the Egyptian ruler Ismail Pasha hired fifty veterans of the American Civil War. Among them was Erastus Sparrow Purdy, a Union Army major who was also an experienced surveyor. Purdy was sent on several expeditions to the south of Egypt and Sudan. In 1870 and 1873 he surveyed the Berenike region. During his second visit to the area he also visited Berenike. With a group of Egyptian soldiers he excavated parts of the temple. Although it is claimed that Purdy excavated the temple in its entirety, precisely how much was unearthed during the 1873 expedition is unclear. After Purdy’s sudden death in 1881 in Cairo his notes of the expedition were never found.

Russian Egyptologist Vladimir Golenischeff traveled to Berenike in 1889, where he saw only traces of the “forecourt”. Golenischeff records the complete decoration of the inner walls of the entrance to room 2, which means that Purdy excavated this part, as Wilkinson did not record the lower half of the double row of nb-signs at the lower end of the inside of the door jambs. This is also the case for room 1, where Wilkinson never fully documented the northern wall. Golenischeff also recorded several niches in the still roofed corridor connecting the “forecourt” with room 4.

Inspector General of the Egyptian Telegraphs Ernest Floyer made the oldest known photograph of the temple in 1891. It shows traces of the early excavations, with the forecourt, room 1 and the corridor entrance partly exposed. The roof of the corridor next to the staircase is still complete.

In 1922 Daressy found and published a copy of Purdy’s temple plan. Daressy pointed out that in the “forecourt” an enormous roof slab was visible. It seems that the copy, probably made by one of the members of the Purdy expedition of 1873, showed more than just a plan, as Daressy’s article also contains several elevations of the temple. Meredith, in his overview of the research of the temple, found the existence of the roof slab unlikely. His main reason was the size of the block, but also because neither Wilkinson, nor Wellsted nor Golenischeff recorded this slab blocking the entrance of the staircase.